Spiral Galaxy NGC 6744

Spiral Galaxy NGC 6744

More Posts from Space-and-stuff-blog1 and Others

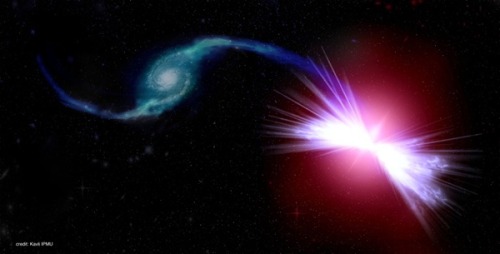

Afraid of Global Warming? Well, now there’s Galactic Warming from our dear friends, those super-massive black holes lurking just about everywhere a galaxy has sprouted up.

These wacky systems are so extreme as to completely skip out of many generations of new stars, leaving a severe stellar age gap in these galaxies, given an entirely new class called “red geysers”.

[First two images are gifs from “Space Engine”, the second is a rendering of the red geyser Akira galaxy sapping off of Tetsuo, it’s neighbor ]

The Special Ingredients…of Earth!

With its blue skies, puffy white clouds, warm beaches and abundant life, planet Earth is a pretty special place. A quick survey of the solar system reveals nothing else like it. But how special is Earth, really?

One way to find out is to look for other worlds like ours elsewhere in the galaxy. Astronomers using our Kepler Space Telescope and other observatories have been doing just that!

In recent years they’ve been finding other planets increasingly similar to Earth, but still none that appear as hospitable as our home world. For those researchers, the search goes on.

Another group of researchers have taken on an entirely different approach. Instead of looking for Earth-like planets, they’ve been looking for Earth-like ingredients. Consider the following:

Our planet is rich in elements such as carbon, oxygen, iron, magnesium, silicon and sulfur…the stuff of rocks, air, oceans and life. Are these elements widespread elsewhere in the universe?

To find out, a team of astronomers led by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), with our participation, used Suzaku. This Japanese X-ray satellite was used to survey a cluster of galaxies located in the direction of the constellation Virgo.

The Virgo cluster is a massive swarm of more than 2,000 galaxies, many similar in appearance to our own Milky Way, located about 54 million light years away. The space between the member galaxies is filled with a diffuse gas, so hot that it glows in X-rays. Instruments onboard Suzaku were able to look at that gas and determine which elements it’s made of.

Reporting their findings in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, they reported findings of iron, magnesium, silicon and sulfur throughout the Virgo galaxy cluster. The elemental ratios are constant throughout the entire volume of the cluster, and roughly consistent with the composition of the sun and most of the stars in our own galaxy.

When the Universe was born in the Big Bang 13.8 billon years ago, elements heavier than carbon were rare. These elements are present today, mainly because of supernova explosions.

Massive stars cook elements such as, carbon, oxygen, iron, magnesium, silicon and sulfur in their hot cores and then spew them far and wide when the stars explode.

According to the observations of Suzaku, the ingredients for making sun-like stars and Earth-like planets have been scattered far and wide by these explosions. Indeed, they appear to be widespread in the cosmos. The elements so important to life on Earth are available on average and in similar relative proportions throughout the bulk of the universe. In other words, the chemical requirements for life are common.

Earth is still special, but according to Suzaku, there might be other special places too. Suzaku recently completed its highly successful mission.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

The dagger that belonged to Pharaoh Tutankhamun has a curious extraterrestrial composition.

King Tut –who ruled over the land of the Pharaohs – continues to amaze the archeological community. Researchers concluded that the iron sheet of the dagger that once belonged to the ‘Boy’ Pharaoh was made from a material that belonged to a meteorite. The scientific study was led by Italian-Egyptian researchers who used X-ray fluorescence to analyze the dagger which dates back to the XIV century BCE.

The mystery behind one of the two daggers found beside the mummy of the Pharaoh is now solved, it originated in space, or better said, the sheet that makes up the dagger was fabricated from materials found in meteorites (source)

Largest Collection of Planets EVER Discovered!

Guess what!? Our Kepler mission has verified 1,284 new planets, which is the single largest finding of planets to date. This gives us hope that somewhere out there, around a star much like ours, we can possibly one day discover another Earth-like planet.

But what exactly does that mean? These planets were previously seen by our spacecraft, but have now been verified. Kepler’s candidates require verification to determine if they are actual planets, and not another object, such as a small star, mimicking a planet. This announcement more than doubles the number of verified planets from Kepler.

Since the discovery of the first planets outside our solar system more than two decades ago, researchers have resorted to a laborious, one-by-one process of verifying suspected planets. These follow-up observations are often time and resource intensive. This latest announcement, however, is based on a statistical analysis method that can be applied to many planet candidates simultaneously.

They employed a technique to assign each Kepler candidate a planet-hood probability percentage – the first such automated computation on this scale, as previous statistical techniques focused only on sub-groups within the greater list of planet candidates identified by Kepler.

What that means in English: Planet candidates can be thought of like bread crumbs. If you drop a few large crumbs on the floor, you can pick them up one by one. But, if you spill a whole bag of tiny crumbs, you’re going to need a broom. This statistical analysis is our broom.

The Basics: Our Kepler space telescope measures the brightness of stars. The data will look like an EKG showing the heart beat. Whenever a planet passes in front of its parent star a viewed from the spacecraft, a tiny pulse or beat is produced. From the repeated beats, we can detect and verify the existence of Earth-size planets and learn about their orbits and sizes. This planet-hunting technique is also known as the Transit Method.

The number of planets by size for all known exoplanets, planets that orbit a sun-like star, can be seen in the above graph. The blue bars represent all previously verified exoplanets by size, while the orange bars represent Kepler’s 1,284 newly validated planets announced on May 10.

While our original Kepler mission has concluded, we have more than 4 years of science collected that produced a remarkable data set that will be used by scientists for decades. The spacecraft itself has been re-purposed for a new mission, called K2 – an extended version of the original Kepler mission to new parts of the sky and new fields of study.

The above visual shows all the missions we’re currently using, and plan to use, in order to continue searching for signs of life beyond Earth.

Following Kepler, we will be launching future missions to continue planet-hunting , such as the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), and the James Webb Space Telescope. We hope to continue searching for other worlds out there and maybe even signs of life-as-we-know-it beyond Earth.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

The Great Red Spot on Jupiter gets smaller by 580 miles per year

-

burnbouquetbarba-blog liked this · 6 years ago

burnbouquetbarba-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

amandarosefay liked this · 6 years ago

amandarosefay liked this · 6 years ago -

jbasiliodn liked this · 7 years ago

jbasiliodn liked this · 7 years ago -

lakesidebear liked this · 8 years ago

lakesidebear liked this · 8 years ago -

aranyaphoenix liked this · 8 years ago

aranyaphoenix liked this · 8 years ago -

raininck liked this · 8 years ago

raininck liked this · 8 years ago -

druidcross liked this · 8 years ago

druidcross liked this · 8 years ago -

juba2205-blog liked this · 8 years ago

juba2205-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

educateyourself310-blog liked this · 8 years ago

educateyourself310-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

gotink56 liked this · 8 years ago

gotink56 liked this · 8 years ago -

tropiques-15 liked this · 8 years ago

tropiques-15 liked this · 8 years ago -

goboldlygeek reblogged this · 8 years ago

goboldlygeek reblogged this · 8 years ago -

i-love-me-too7-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

i-love-me-too7-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

victoriabelenfranzoi-blog liked this · 8 years ago

victoriabelenfranzoi-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

pityandcigarettes reblogged this · 8 years ago

pityandcigarettes reblogged this · 8 years ago -

pityandcigarettes liked this · 8 years ago

pityandcigarettes liked this · 8 years ago -

yacare2 liked this · 8 years ago

yacare2 liked this · 8 years ago -

eighteenthdream liked this · 8 years ago

eighteenthdream liked this · 8 years ago -

kawaiimittenz-blog liked this · 8 years ago

kawaiimittenz-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

vampirebatreblog liked this · 8 years ago

vampirebatreblog liked this · 8 years ago -

mechanicsofconsciousness reblogged this · 8 years ago

mechanicsofconsciousness reblogged this · 8 years ago -

pervalien liked this · 8 years ago

pervalien liked this · 8 years ago -

ineedtoquenchmythirst liked this · 8 years ago

ineedtoquenchmythirst liked this · 8 years ago -

ineedtoquenchmythirst reblogged this · 8 years ago

ineedtoquenchmythirst reblogged this · 8 years ago -

butterflies-and-muse liked this · 8 years ago

butterflies-and-muse liked this · 8 years ago -

acuariopsiquiatrico reblogged this · 8 years ago

acuariopsiquiatrico reblogged this · 8 years ago -

idontknowwhattocallthisposts liked this · 8 years ago

idontknowwhattocallthisposts liked this · 8 years ago -

loonieytunez reblogged this · 8 years ago

loonieytunez reblogged this · 8 years ago -

cocoatunda liked this · 8 years ago

cocoatunda liked this · 8 years ago -

falatiopro reblogged this · 8 years ago

falatiopro reblogged this · 8 years ago -

calrhyo liked this · 8 years ago

calrhyo liked this · 8 years ago -

calrhyo reblogged this · 8 years ago

calrhyo reblogged this · 8 years ago -

originalchildmilkshake-blog liked this · 8 years ago

originalchildmilkshake-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

thcapc liked this · 8 years ago

thcapc liked this · 8 years ago -

anonywes liked this · 8 years ago

anonywes liked this · 8 years ago -

a-blog-of-void liked this · 8 years ago

a-blog-of-void liked this · 8 years ago -

oh-sarahjane reblogged this · 8 years ago

oh-sarahjane reblogged this · 8 years ago -

oh-sarahjane liked this · 8 years ago

oh-sarahjane liked this · 8 years ago -

rattatitties liked this · 8 years ago

rattatitties liked this · 8 years ago

Just Space, math/science and nature. Sometimes other things unrelated may pop up.

119 posts