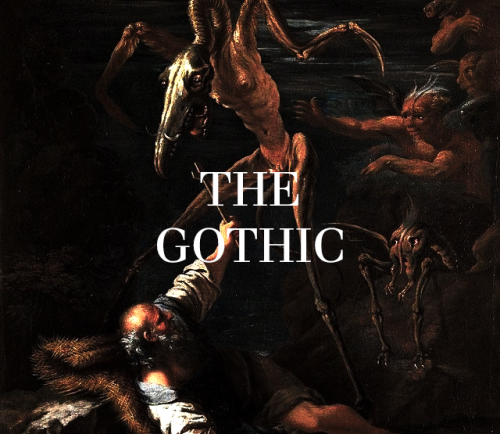

Masterpost Of Free Gothic Literature & Theory

Masterpost of Free Gothic Literature & Theory

Classics Vathek by William Beckford Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë The Woman in White & The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu The Turn of the Screw by Henry James The Monk by Matthew Lewis The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Maturin The Vampyre; a Tale by John Polidori Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe Confessions of an English Opium-Eater by Thomas De Quincey The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson Dracula by Bram Stoker The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

Short Stories and Poems An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge by Ambrose Bierce Songs of Innocence & Songs of Experience by William Blake The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge The King in Yellow by Robert W. Chambers The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Pre-Gothic Beowulf The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe Paradise Lost by John Milton Macbeth by William Shakespeare Oedipus, King of Thebes by Sophocles The Duchess of Malfi by John Webster

Gothic-Adjacent Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen The Wendigo by Algernon Blackwood Jane Eyre & Villette by Charlotte Brontë Lyrical Ballads, With a Few Other Poems by Coleridge and Wordsworth The Mystery of Edwin Drood by Charles Dickens The Idiot & Demons (The Possessed) by Fyodor Dostoyevsky The Man in the Iron Mask by Alexandre Dumas Moby-Dick by Herman Melville The Island of Doctor Moreau by H. G. Wells

Historical Theory and Background The French Revolution of 1789 by John S. C. Abbott Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth by A. C. Bradley The Tale of Terror: A Study of the Gothic Romance by Edith Birkhead On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History by Thomas Carlyle Demonology and Devil-Lore by Moncure Daniel Conway Ancient Pagan and Modern Christian Symbolism by Inman and Newton On Liberty by John Stuart Mill The Social Contract & Discourses by Jean-Jacques Rousseau Feminism in Greek Literature from Homer to Aristotle by Frederick Wright

Academic Theory Introduction: Replicating Bodies in Nineteenth-Century Science and Culture by Will Abberley Viewpoint: Transatlantic Scholarship on Victorian Literature and Culture by Isobel Armstrong Theories of Space and the Nineteenth-Century Novel by Isobel Armstrong The Higher Spaces of the Late Nineteenth-Century Novel by Mark Blacklock The Shipwrecked salvation, metaphor of penance in the Catalan gothic by Marta Nuet Blanch Marching towards Destruction: the Crowd in Urban Gothic by Christophe Chambost Women, Power and Conflict: The Gothic heroine and “Chocolate-box Gothic” by Avril Horner Psychos’ Haunting Memories: A(n) (Un)common Literary Heritage by Maria Antónia Lima ‘Thrilled with Chilly Horror’: A Formulaic Pattern in Gothic Fiction by Aguirre Manuel The terms “Gothic” and “Neogothic” in the context of Literary History by O. V. Razumovskaja The Female Vampires and the Uncanny Childhood by Gabriele Scalessa Curating Gothic Nightmares by Heather Tilley Elizabeth Bowen, Modernism, and the Spectre of Anglo-Ireland by James F. Wurtz Hesitation, Projection and Desire: The Fictionalizing ‘as if…’ in Dostoevskii’s Early Works by Sarah J. Young Intermediality and polymorphism of narratives in the Gothic tradition by Ihina Zoia

More Posts from Moominnie11 and Others

And even second-grade Vietnamese can be abused. “In the Vietnamese context — and it might be similar to Chinese — words are like spells,” Vuong told the writer Hua Hsu in 2022, claiming English speakers have a basically primitive relationship to language compared with the peoples of the Far East. This is deeply insulting to Vuong’s much-invoked illiterate ancestors, who were apparently so in touch with the primordial metaphors that they never managed to convey basic information to one another. Of course, what can make the mother tongue seem like magic is the simple fact that one does not speak it very well. Like many children of diaspora — I include myself here — Vuong mistakes his own naïveté for insight.

Tiles, Gustav Klimt

When I first got into writing, I found myself struggling with all these character profile sheets that asked for descriptors like favorite color or favorite tattoos. Don't get me wrong - the fun in creating these profiles is bringing them to life in your author-ly mind. But when I finally hit the pages, I realized that my characters' interiority is what made each of them so memorable to me and my readers. Here are some questions I think could be worth asking of your characters before you try writing a chapter with them:

Who do they go to when they hit a low point? If not who, then where?

How do they react when someone compliments them?

They have to do some spring cleaning. What are they tossing?

What’s their go-to spot for a date (romantic or platonic)?

How do they react when they’re slighted? Do they totally rage out, plot something for later, or move past their feelings?

Who will they cry in front of?

What do they consider to be some of the cruelest injustices in the world?

What’s the first thing they’ve ever owned?

How do they relax during their down time?

What personal misconception gets in the way of them achieving what they want?

Do they love anyone?

Do they hate anyone?

How do they comfort others?

What brings them comfort?

Do new skills come easily to them, or does it take perseverance?

Who and/or what cause are they willing to blow their lives up for?

What rumors are attached to them?

What soothes them?

Do they like to share?

What is their calling?

Hope this helps!

“As no science explains adequately how dreams work, no one can explain how a poem works. Where is a dream, sure, but where is a poem? I believe somewhat in Williams’ formulation that a poem is a machine made out of words, but, finally, the poem isn’t where the words are. The poem is somewhere between the words and the reader, or it is the words taken into the reader, who exists within the general society and its history. You enter the poem when you open to its page or remember it, having memorized it, but it is a much larger world than the page. It is transformed when you say it out loud; and it changes from reading to reading—you, the reader, change it, for one thing, as you change—or is it that it changes for you? If you are reading a poem by Catullus, you are in no way the same as an ancient Roman reading it: you are not that person—that kind of person, though it is that poem, as those words. But even if you know Latin, you don’t “speak Latin,” and you haven’t much feeling for what it was like to be a Roman. A poem, like a dream, has an odd relation to time: it is in time, like a poem by Catullus, but it is timeless, as an object made out of words. A dream lasts a moment but endures as a memory might: but it didn’t really happen. A memory can be backed-up, but no outside observer can find the particulars of a dream in time and space (evidence of REM or whatever isn’t evidence of what happened in your dream). A poem didn’t or doesn’t happen, it’s a still group of words on a page; and a story doesn’t really happen either. We say that dreams, poems, and stories occur in the imagination, or the psyche, or whatever word we’re using right now, to invent another entity that doesn’t concretely exist to put them in. But doesn’t the “real world” exist in some collective category like that? All we do is dream; we live in poems and stories we invent.”

— Alice Notley on Writing from Dreams ‹ Literary Hub

𝔬𝔫𝔩𝔶 𝔰𝔩𝔦𝔤𝔥𝔱𝔩𝔶 𝔥𝔞𝔲𝔫𝔱𝔢𝔡

んにゃわけにゃいにゃ

Sometimes the grief really is love persevering huh

and all i loved, i loved alone

mugs by Atesartt

-

assassin-sadboy reblogged this · 1 week ago

assassin-sadboy reblogged this · 1 week ago -

misskittygrimm liked this · 1 week ago

misskittygrimm liked this · 1 week ago -

is-this-gray liked this · 1 week ago

is-this-gray liked this · 1 week ago -

allisonkittel liked this · 1 week ago

allisonkittel liked this · 1 week ago -

becoming-that-boy reblogged this · 1 week ago

becoming-that-boy reblogged this · 1 week ago -

moominnie11 reblogged this · 1 week ago

moominnie11 reblogged this · 1 week ago -

crownprinceknut liked this · 1 week ago

crownprinceknut liked this · 1 week ago -

makingmyriapodsmirthful reblogged this · 1 week ago

makingmyriapodsmirthful reblogged this · 1 week ago -

mifhortunach reblogged this · 1 week ago

mifhortunach reblogged this · 1 week ago -

cemterygates liked this · 1 week ago

cemterygates liked this · 1 week ago -

transpathfinder reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

transpathfinder reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

madeofstarsdust liked this · 3 weeks ago

madeofstarsdust liked this · 3 weeks ago -

nokashikiari liked this · 3 weeks ago

nokashikiari liked this · 3 weeks ago -

epifaniacintilante liked this · 3 weeks ago

epifaniacintilante liked this · 3 weeks ago -

akanague reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

akanague reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

akanague liked this · 3 weeks ago

akanague liked this · 3 weeks ago -

archivedduck reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

archivedduck reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

firstservantmurdered reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

firstservantmurdered reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

returntoweebdom liked this · 3 weeks ago

returntoweebdom liked this · 3 weeks ago -

returntoweebdom reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

returntoweebdom reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

readinglover liked this · 3 weeks ago

readinglover liked this · 3 weeks ago -

anotherspookyarchivist liked this · 3 weeks ago

anotherspookyarchivist liked this · 3 weeks ago -

miskapestek reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

miskapestek reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

miskapestek liked this · 3 weeks ago

miskapestek liked this · 3 weeks ago -

cawareyoudoin reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

cawareyoudoin reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

cawareyoudoin liked this · 3 weeks ago

cawareyoudoin liked this · 3 weeks ago -

dedtek liked this · 4 weeks ago

dedtek liked this · 4 weeks ago -

voidstation liked this · 4 weeks ago

voidstation liked this · 4 weeks ago -

snailnamedcloud reblogged this · 1 month ago

snailnamedcloud reblogged this · 1 month ago -

yon0pedinacer reblogged this · 1 month ago

yon0pedinacer reblogged this · 1 month ago -

dancingafterdark liked this · 1 month ago

dancingafterdark liked this · 1 month ago -

the-water-fae liked this · 1 month ago

the-water-fae liked this · 1 month ago -

lovelybenny liked this · 1 month ago

lovelybenny liked this · 1 month ago -

shiningmiracles reblogged this · 1 month ago

shiningmiracles reblogged this · 1 month ago -

coffinwebs liked this · 1 month ago

coffinwebs liked this · 1 month ago -

buridanshorse reblogged this · 1 month ago

buridanshorse reblogged this · 1 month ago -

cremedeco liked this · 1 month ago

cremedeco liked this · 1 month ago -

sang-d-or liked this · 1 month ago

sang-d-or liked this · 1 month ago -

romanticize-and-decay reblogged this · 1 month ago

romanticize-and-decay reblogged this · 1 month ago -

justaghouletteintheclergy reblogged this · 1 month ago

justaghouletteintheclergy reblogged this · 1 month ago -

litten456 liked this · 1 month ago

litten456 liked this · 1 month ago -

couldibeyou reblogged this · 2 months ago

couldibeyou reblogged this · 2 months ago -

kdreader02 liked this · 2 months ago

kdreader02 liked this · 2 months ago -

abandonedaetheremporium liked this · 2 months ago

abandonedaetheremporium liked this · 2 months ago -

moonsintwo liked this · 2 months ago

moonsintwo liked this · 2 months ago