I’m Convinced This Is The Moment Crowley Fell In Love.

I’m convinced this is the moment Crowley fell in love.

More Posts from Kaanha-ki-barkat and Others

The new-TV-GoodOmens fanon tendency to take Aziraphale’s very-soft presentation as unadorned truth is be/amusing to me.

He was the angel left to guard one of the Gates to Eden and he did in fact have a flaming sword. He is also the one who WOULD have shot Adam, had Madame Tracy not intervened.

He is also the angel who’s response to “wait I need to get back to Earth to stop Armageddon” is to do something that clearly SCARED THE SHIT out of the other angels who watched him do it, with a malicious-glee-glint in his eye, who hopped disembodied down to earth, and then floated around to try to find the right place.

He also, well. Fucked around with Heaven at all. There’s such a thread of comic corporate-absurd involved that it can be easy to miss, but what we’re shown is that the hierarchy of Heaven is just as happy as that of Hell to murder, torture, restrain, make captive and otherwise punish its own in the most horrible ways possible and in fact they’re far more effective at it. They just have a lot of Rules they follow, whereas Hell acts on a whim.

And there’s Aziraphale running around lying to them and pulling the wool over their eyes and so on. Something which, very clearly, none of those other angels are interested in doing.

Fundamentally Aziraphale is a stone cold agent of divine wroth.

He just doesn’t want to be.

He doesn’t like being like that. He doesn’t like suffering, his own or other people’s. All those times Crowley saves him, it’s important to keep in mind that Aziraphale’s in no more fundamental danger than he is when he loses his corporal form in the bookshop fire: if Crowley hadn’t shown up to save him in the church, for example, all that would have happened is that either a) he would have been discorporated and had to wait in line for a new body (or risk being reassigned) or b) Aziraphale would have had to do something Nasty to the Nazis there in order to save himself that trouble.

He doesn’t like either of those options! Those are both crappy options. But they’re not existential threats.

I’m the nice one he snaps when Crowley’s too busy having his Moment over his Bentley to take care of dealing with the soldier.

Aziraphale doesn’t like having to be cruel, or mean, or scary, or stone cold. He doesn’t enjoy it and given the choice he will in fact choose not to be.

What Crowley saves him from, over and over again, isn’t actually being killed.

Because what interests Crowley in him, and we see that, all the way back, is that very first instance of Aziraphale choosing not to be that person. That first time when what Aziraphale was supposed to be was Stern and Frightening and Judgemental and Harsh and Terrifying … . and instead he chose to court potential punishment (and actual existential threat) to give the people he was supposed to Terrify a way to protect themselves from all the scary things.

Aziraphale doesn’t want to be an instrument of judgement and wrath and what Crowley keeps saving him from is having to be. Crowley condemns the bloodthirsty executioner, so that Aziraphale doesn’t have to; blows up the Nazis so Aziraphale doesn’t have to.

Lets Aziraphale be the nice one, in fact.

Which I think is frankly far more fucking adorable.

But never let it make you think that Aziraphale is the safe one, or the helpless one.

He’s the one who, when faced with the apparent choice between killing a child and the end of the world, chooses to kill the child. Actually chooses to do it - not just plan, not just talk about, not just contemplate, but do it - and is only saved from having done it by sharing the body of someone who won’t let him.

Aziraphale is soft and slightly silly and gentle and non-confrontational and all of those things because that’s what he wants to be. He has fought for a long time to get to be that.

This is important.

Baby armadillo.

Movie Rec: "Jab We Met" (Bollywood)

“Jab We Met” is a pretty traditional romance narrative at surface level, which is also quietly but very effectively subverting a lot of the common romance tropes. It’s one of my favorite Bollywood movies, but it’s rarely one that I use to convert people mostly because it isn’t a movie that could only exist in Bollywood. It’s a pretty universally awesome romance narrative, all around.

HOWEVER, there is an aspect of it that makes it more subversive given the cultural context, which is that the heroine, while wanting a romantic happy ending for herself, wants one that’s traditionally frowned upon by her culture.

While the narrative starts with the premise of a Brooding Hero meeting his Manic Pixie Dreamgirl, that’s where the similarities end. Because we find out a lot more about Geet, her hopes and dreams, and her family than we ever do about him. One of the only things we do know about him is that at some point in his childhood, his mother ran off with another man because she didn’t love his father. The language used to describe her elopement will give you an idea of just how huge of a deal elopement is in this culture, and what kind of social disgrace Geet is possibly setting herself up for by wanting to elope.

However, the movie has Geet identifying with the mother pretty early on, and before the movie ends, this turns into an epic commentary on women and their choices and about doing what makes you happy rather than following social conventions that stifle you. So the most important thing we DO know about him still becomes about her. <3

I never have much to say about men in fiction, but the male protagonist of this movie is one that I quite like. He spends a good part of the movie being in love with her, but never even telling her, because he sees that as his own issue, and nothing *she* should be burdened with. Like, he has ZERO need for his feelings for her to be validated or returned. Which NEVER happens in romance narrative (except for in “Pride and Prejudice,” and that’s why it’s my favorite.)

And Geet! <3 Geet is one of the most self-assured and confident heroines I have ever come across in any narrative. She knows what she wants, and she has no hesitation or doubts about how she’s going to get it. She has a strong sense of self that briefly wavers in the face of the utter force of everything that’s against her, but comes back stronger than ever.

This is, by all means, set up as a narrative where the heroine would Learn Her Lesson about Wanting Unconventional Things, but the entire movie sets out to show HER way of life as the correct one, with everyone around her adapting to her worldview. Even though the specifics of what she wants for herself change, she still gets the exact kind of happy ending she set out to chase for herself.

I also love her need to create drama and constantly strive to write out a more interesting narrative for herself than the one life would otherwise give her. She reminds me of Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse or Catherine Morland, except that both of these women had to learn a lesson about Needing to be Serious/Mature (from the men they loved), while Geet keeps on being herself, and the guy has to change himself to adapt to her viewpoint. <3

Like, the speech that both Emma and Catherine get from the Men Who Love Them and Know Better? Geet gets that about halfway through the movie, only to totally set the guy straight, and that is literally the actual moment he falls for her. BECAUSE SHE REFUSED TO SUBSCRIBE TO HIS WORLD VIEW. And then he subscribes to her awesomeness. You should, too.

It's a Buffalo calf indeed! Nadia Afgan (Shahana) retweeted a gif in which someone was trying to catch hold and control a Buffalo, so it's actually funnier as you said 😂😂😂

Hey TT! I hope you are doing great. In nava katta, katta= buffalo calf. Love from Pakistan

Oh! Thanks for clarifying! I knew that “katta” meant buffalo (because lol Shahana explained “doobi katta” in the last season) but I thought it also meant something that could be tied and untied (coz BiJaan said “maayke bhej doongi toh, kholti aur baandti rehna apne katte wahaan”) So when they say “nawa katta khul gaya” it actually means that a buffalo calf has been untied and is running free? Lmao that’s even funnier! 🤣🤣🤣

Tum se hi

Aankhon mein aankhen teri, baahon mein baahein teri,

mera na mujh mein kuch raha,

hua kya?

Baaton mein baatein teri, raatein saugatein teri,

kyun tera sab yeh ho gaya?

Hua kya?

Dedicated to the brilliant @ferociouspompom , for being my fave person in the whole wide world. Geet has nothing on you! ;)

On a few occurences in the book, it gets mentionned that Aziraphale has manicured hands, and I’ve been fixating on it ever since. I wrote this small fic focusing on this very detail, hope you guys enjoy !

———————————————————————————————————–

Aziraphale, as it was, was not exactly into fashion. However, he did like the idea of expressing one’s personnality through what they were wearing. But, unlike Crowley, he couldn’t bring himself to just change radically every decade. It wasn’t very Aziraphale. The change. Not when it was too drastic, at least. The idea came to him when the first nail salons blossomed in London.

Keep reading

Abhimanyu;

❝Once, a star was left to burn itself to ash. Once, a star was trapped in a bottle and set aflame.❞

from [xxx] by muskurahat.

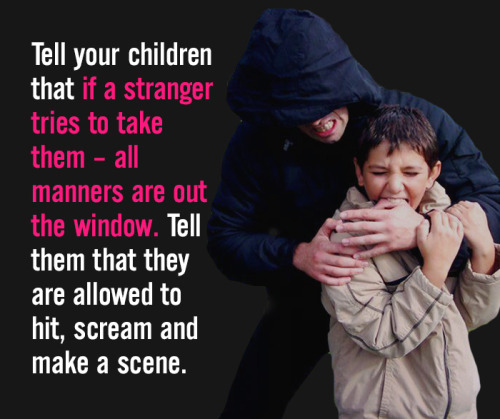

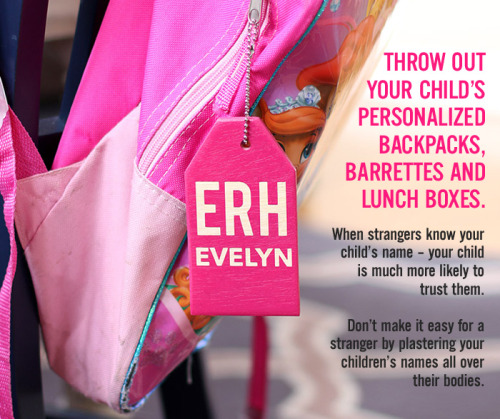

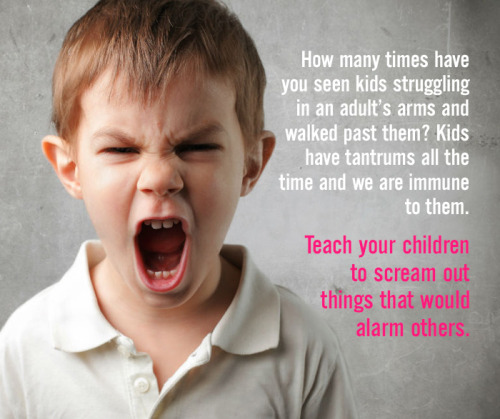

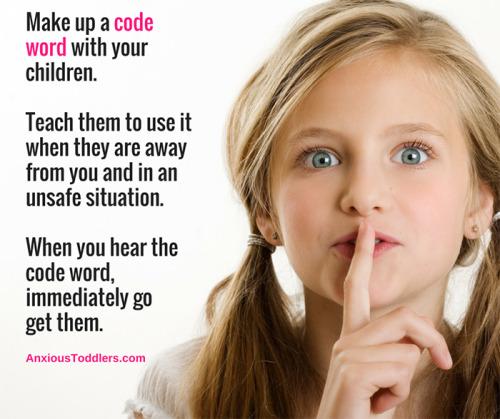

Tips That Can Save Your Kid’s Life.

Crowley, teaching Aziraphale to drive: Okay, so you’re driving and Gabriel and Michael walk onto the road. Quick, what do you hit?

Aziraphale: Oh definitely Gabriel

Crowley, sighing: The brakes, angel. You hit the brakes.

Rama and Krishna trading places

for @medhasree

“You killed him,” says one of Kaliya’s wives in a voice devoid of all feeling, even as her husband sinks deeper into the waters of the Yamuna. “He was poisoning our waters, and the very air we breathe,” Balarama says, even as his heart yearns after the greatest part of him lying coiled at the edge of the universe. Almost he could slip into the waters himself and, unaffected, slip his arms around his kinswomen to comfort them. Rama, on the banks, cleans his arrows and slips them into a quiver comically big for him, and says, “I killed him, as I kill all monsters who trouble my people.” “We are ourselves everywhere hunted by Garuda,”another wife protests. “If you retaliate by poisoning mortals, you turn from victims to villains yourself. Betake yourselves to Ramanaka Island, and live unharmed.”

“I would love nothing more,” Krishna reassures Surpanakha, “for I cannot remember when last I saw a woman so divinely lovely, bedecked in all the treasures the world can offer and yet needing none to add to her own beauty.” The rakshasi pauses, and the following smile has a distinct gleam of fangs. “You flatter masterfully, mortal, but I can hear a lie. You would love nothing more, yet surely you will find a reason to refuse me.” “I would love nothing more,” Krishna repeats, “but I have a wife already.” “An obstacle easily removed,” Surpanakha suggests, grinning wider than her slender face should allow. Lakshmana springs to his feet, outraged, but then sits again, arrow unnocked, at Krishna’s amused gesture. “But if you kill her I would mourn a hundred summers and scarcely be in a mood for love. You are far too intelligent to think otherwise.” “Since when do mortal men limit themselves to a single wife?” the rakshasi queries. Krishna grins back at her, sunny and careless. “My own father has three queens, and the jealousy of one has brought us to this forest. So I cannot take you for a wife unless you renounce your royal life and live with us as a mendicant, for to do otherwise would cause resentment in my wife. Yet I cannot ask you to sacrifice your life and all its many enjoyments to live with us as my wife does, for that would anger you. You see my dilemma?” “I… yes,” says Surpanakha. “I will have your brother then, if I cannot have you.” “You could marry him,” Krishna allows. “But he is sworn to celibacy, so I would not advise it for one so given to pleasure as you are, O sensuous one.”

“Of course we will fight for you, with all the might Dwaraka has,” Rama assures the Pandavas. “I could hardly do less when my kinsmen are offered insult, and one I have long called a sister.” “One might argue,” says Prince Satyajit, “that it was Yudhishtira who offered insult to our sister, by waging her as he might his slaves.” It is the position Panchal has been taking on the matter, Panchali not excepted, and even Yudhishtira has grown inured enough to offer no ,ore than a tired flinch. “If he were playing against an honourable man, such a wager would not have been accepted, any more than you would trust a drunkard with your beloved child,” Rama says. “It makes no matter; we go to war not for petty faults, but because of dharma and adharma.” “Then must we wait,” Draupadi asks, “while the world grows heavy with adharma? What keeps us from war this instant?” “A vow binds you,” Rama reminds her, gentle and inexorable as a god. “But it does not bind us,” Satyajit points out. Rama’s answering laugh lights up the day, shakes birds from the trees.

Krishna is the one who fetches his wife from the Asoka grove, swings her off her feet laughing, kisses the tears from her eyes, and tells her, “I know this will be difficult for you after all our years in seclusion, but we must do it for the army, and to stifle any rumours before they raise their heads.” In front of the army he embraces her again, this time a conquering hero and not a relieved husband, and says in the voice that massed regiments can hear in the din of battle, “Now is my life lit up again, with Janaka’s chaste daughter in my arms. All my war has been but for this, that I may have my wife by my side once more.”

-

zukoandhisdragon liked this · 3 months ago

zukoandhisdragon liked this · 3 months ago -

lulusantosreal liked this · 3 months ago

lulusantosreal liked this · 3 months ago -

lulusantosreal reblogged this · 3 months ago

lulusantosreal reblogged this · 3 months ago -

alwysthere42 liked this · 3 months ago

alwysthere42 liked this · 3 months ago -

smitten-like-anything liked this · 4 months ago

smitten-like-anything liked this · 4 months ago -

holy-cockamole liked this · 5 months ago

holy-cockamole liked this · 5 months ago -

hook-excho-squall-bankfull liked this · 5 months ago

hook-excho-squall-bankfull liked this · 5 months ago -

digitalmeowmix reblogged this · 5 months ago

digitalmeowmix reblogged this · 5 months ago -

digitalmeowmix liked this · 5 months ago

digitalmeowmix liked this · 5 months ago -

kyouya-mon-ami liked this · 5 months ago

kyouya-mon-ami liked this · 5 months ago -

rkoradiopictures reblogged this · 6 months ago

rkoradiopictures reblogged this · 6 months ago -

limpnoodles liked this · 10 months ago

limpnoodles liked this · 10 months ago -

luminaraonwheels liked this · 10 months ago

luminaraonwheels liked this · 10 months ago -

rainbowpopeworld liked this · 11 months ago

rainbowpopeworld liked this · 11 months ago -

colorfuloddity liked this · 11 months ago

colorfuloddity liked this · 11 months ago -

lazulibundtcake reblogged this · 11 months ago

lazulibundtcake reblogged this · 11 months ago -

rarlya liked this · 11 months ago

rarlya liked this · 11 months ago -

anigrim liked this · 11 months ago

anigrim liked this · 11 months ago -

jcshellyg liked this · 1 year ago

jcshellyg liked this · 1 year ago -

notjustamumj reblogged this · 1 year ago

notjustamumj reblogged this · 1 year ago -

fanishjuli reblogged this · 1 year ago

fanishjuli reblogged this · 1 year ago -

fuck-you-gaiman reblogged this · 1 year ago

fuck-you-gaiman reblogged this · 1 year ago -

regulus-plop-plop liked this · 1 year ago

regulus-plop-plop liked this · 1 year ago -

asterism-unknown liked this · 1 year ago

asterism-unknown liked this · 1 year ago -

morally-gray101 reblogged this · 1 year ago

morally-gray101 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

morally-gray101 liked this · 1 year ago

morally-gray101 liked this · 1 year ago -

maddeningmagic106 reblogged this · 1 year ago

maddeningmagic106 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

fuck-you-gaiman liked this · 1 year ago

fuck-you-gaiman liked this · 1 year ago -

reybeeze liked this · 1 year ago

reybeeze liked this · 1 year ago -

a-myriad-of-flowers liked this · 1 year ago

a-myriad-of-flowers liked this · 1 year ago -

phil-the-destroyer-of-worlds liked this · 1 year ago

phil-the-destroyer-of-worlds liked this · 1 year ago -

we-are-falling-through-space reblogged this · 1 year ago

we-are-falling-through-space reblogged this · 1 year ago -

moedenlark liked this · 1 year ago

moedenlark liked this · 1 year ago -

chaotic-jupiter liked this · 1 year ago

chaotic-jupiter liked this · 1 year ago -

killingermillo liked this · 1 year ago

killingermillo liked this · 1 year ago -

longwayfromstarfleet liked this · 1 year ago

longwayfromstarfleet liked this · 1 year ago -

monicacox4d liked this · 1 year ago

monicacox4d liked this · 1 year ago -

sir-thursday-iii liked this · 1 year ago

sir-thursday-iii liked this · 1 year ago -

moongirl4816 liked this · 1 year ago

moongirl4816 liked this · 1 year ago -

halfhumanhalfasleep liked this · 1 year ago

halfhumanhalfasleep liked this · 1 year ago -

totheshipsthatneversailed reblogged this · 1 year ago

totheshipsthatneversailed reblogged this · 1 year ago -

lillyfell liked this · 1 year ago

lillyfell liked this · 1 year ago -

ilmarievie09 liked this · 1 year ago

ilmarievie09 liked this · 1 year ago -

dochsamuraya1986-blog liked this · 1 year ago

dochsamuraya1986-blog liked this · 1 year ago -

szethsmom liked this · 1 year ago

szethsmom liked this · 1 year ago -

playablekairi liked this · 1 year ago

playablekairi liked this · 1 year ago -

gayforaziracrow liked this · 1 year ago

gayforaziracrow liked this · 1 year ago -

curiouswriterkr liked this · 1 year ago

curiouswriterkr liked this · 1 year ago -

heavensrepublic liked this · 1 year ago

heavensrepublic liked this · 1 year ago -

thisisnotjuli liked this · 1 year ago

thisisnotjuli liked this · 1 year ago

227 posts